Reserve

Reserve prices in all-pay auctions with complete information Dipartimento di economia politica e metodi quantitativi We introduce reserve prices in the literature concerning all-pay auctions with complete information, and reconsider the case for the so-called Exclusion Principle (namely, the fact that the seller may find it in her best interest to exclude the bidders with the largest willin

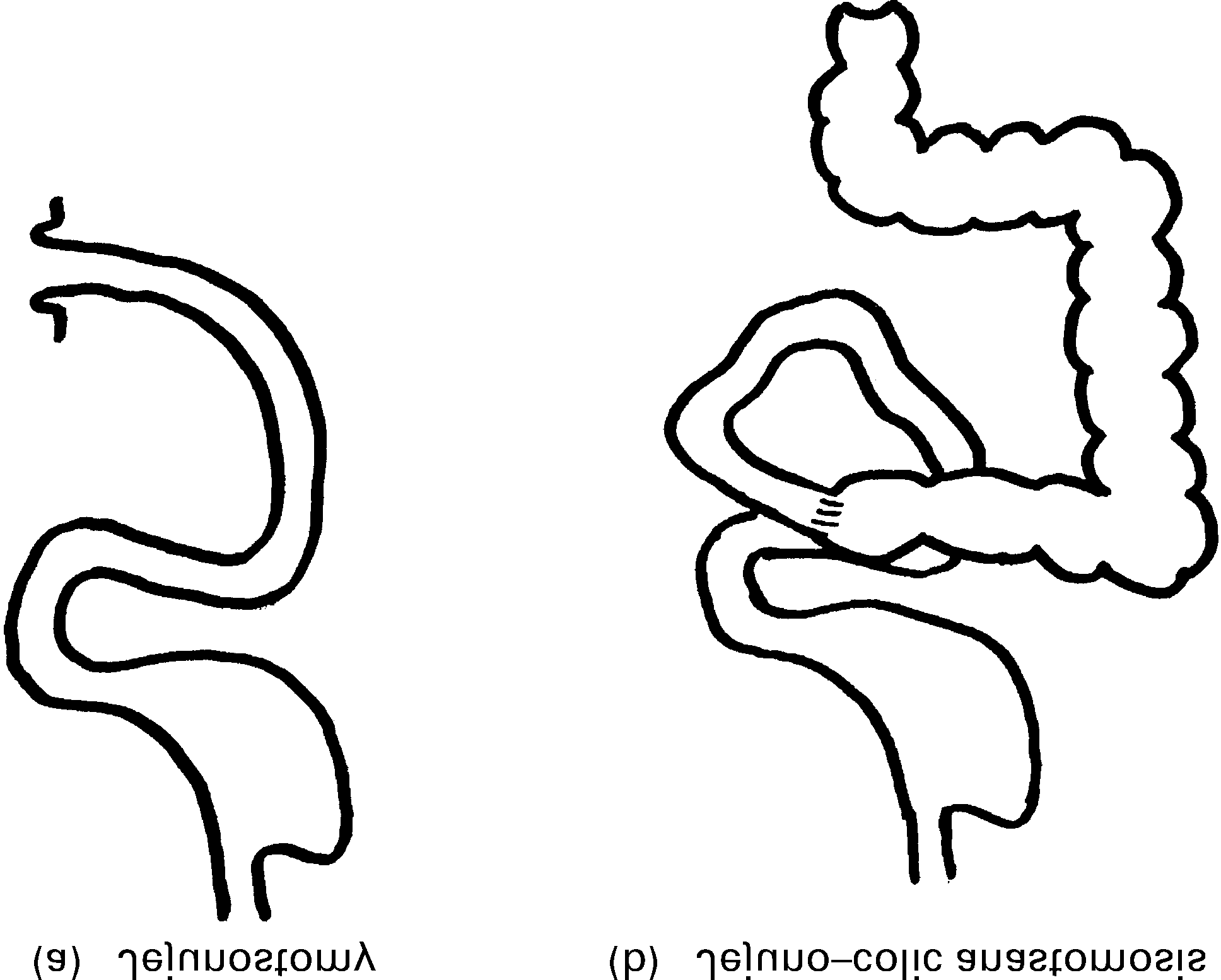

Methods for reducing the severity of chronic intestinal

Methods for reducing the severity of chronic intestinal