Microsoft word - trabajos de cada tesis

Tesis Dra. Aranzazu González Canga: 1. Intravenous pharmacokinetics of ivermectin in sheep and goats. González A, García JJ, Sierra M, Fernández N, Castro LJ, Sahagún A. Meth Find Exp Clin Pharmacol 2004:26;127. 2. Subcutaneous bioavailability of a new commercial formulation of ivermectin in goats. González A, García JJ, Diez MJ, Castro LJ, Sierra M, Sahagún A. Meth Find Exp Clin Ph

However, evidence that obesity also affects the chance of

spontaneous pregnancy in subfertile ovulatory women is still

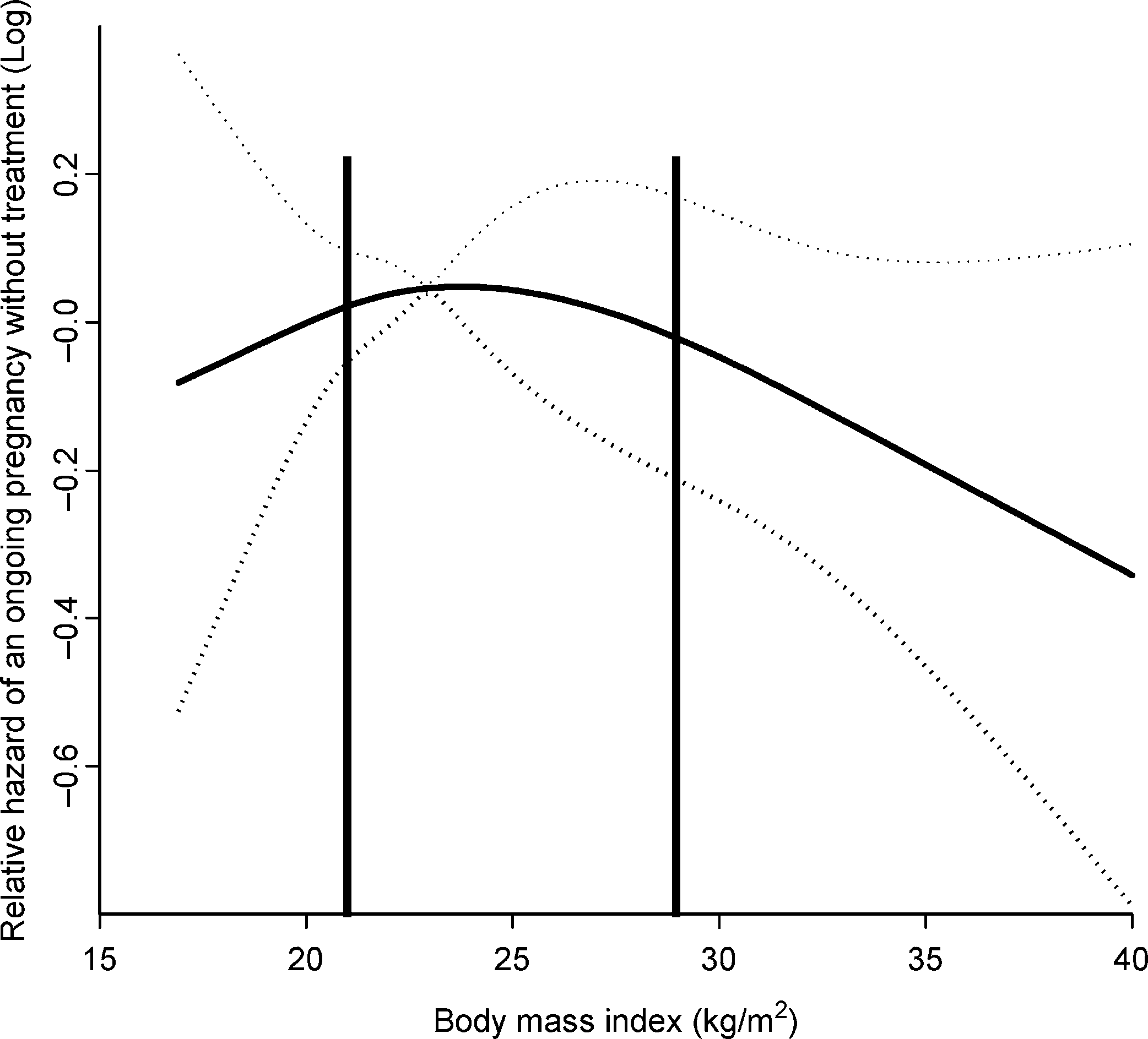

We first assessed the relation between BMI and probability of preg-

lacking. The aim of this study was to determine whether

nancy through spline functions. By visual inspection, it was deter-

obesity in subfertile ovulatory women is associated with a

mined whether BMI behaved as a linear or non-linear function in

decreased chance of spontaneous pregnancy.

However, evidence that obesity also affects the chance of

spontaneous pregnancy in subfertile ovulatory women is still

We first assessed the relation between BMI and probability of preg-

lacking. The aim of this study was to determine whether

nancy through spline functions. By visual inspection, it was deter-

obesity in subfertile ovulatory women is associated with a

mined whether BMI behaved as a linear or non-linear function in

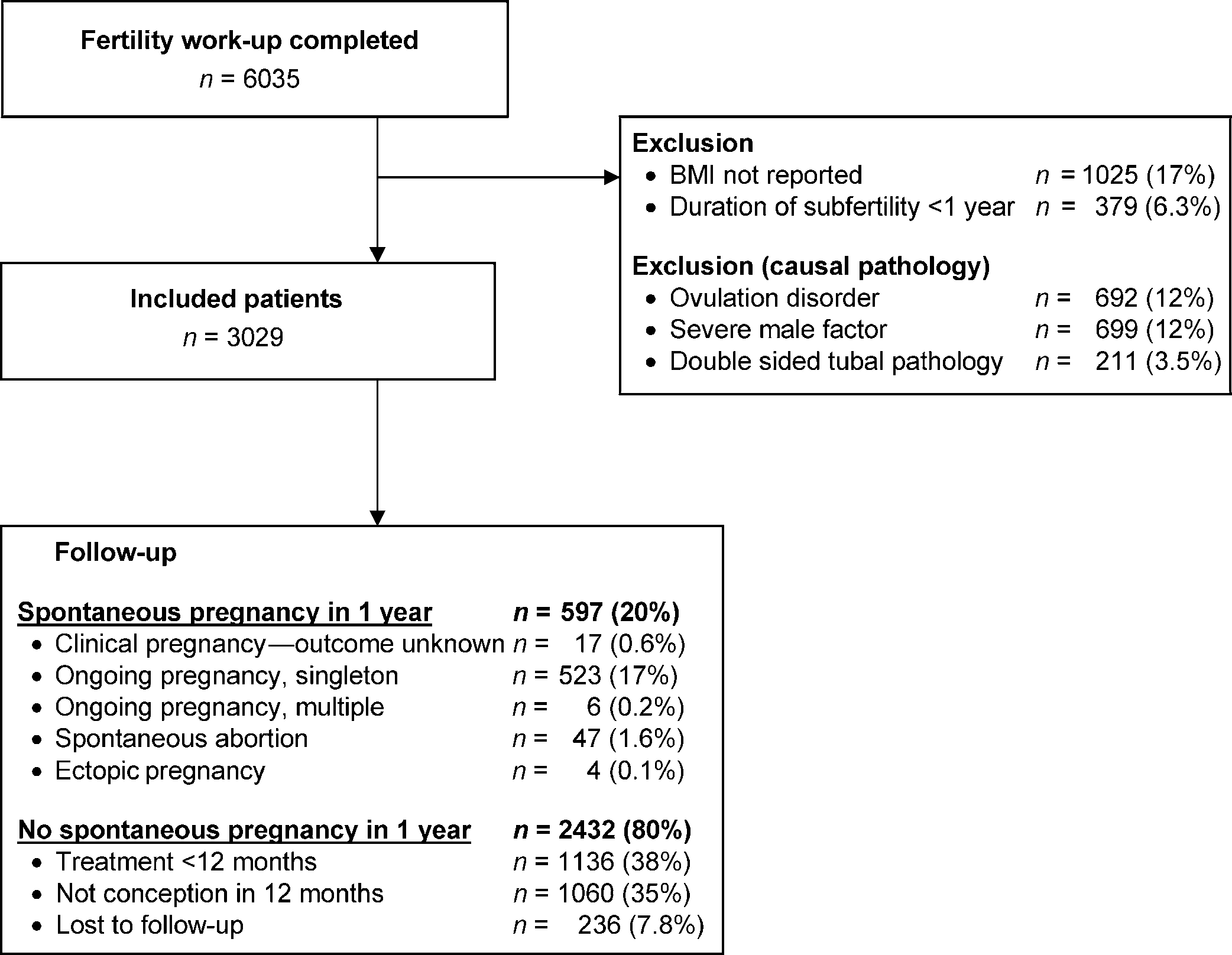

decreased chance of spontaneous pregnancy. 1136 (38%) couples started treatment, whereas 1060 (35%)

29 kg/m2 (95% CI 0.91 – 0.99)]. A BMI below 21 kg/m2 was

neither started treatment nor became pregnant. Median length

associated with a lower probability of spontaneous ongoing

of follow-up was 28.1 weeks (fifth to 95th percentile: 2 – 134

pregnancy than the reference group, but was not statistically

weeks), 18.5 weeks (1 – 100 weeks) for those who conceived

significant [HR 0.97 per kg/m2 below 21 kg/m2 (95% CI

and 31.5 weeks (2 – 146 weeks) for those without a pregnancy.

1136 (38%) couples started treatment, whereas 1060 (35%)

29 kg/m2 (95% CI 0.91 – 0.99)]. A BMI below 21 kg/m2 was

neither started treatment nor became pregnant. Median length

associated with a lower probability of spontaneous ongoing

of follow-up was 28.1 weeks (fifth to 95th percentile: 2 – 134

pregnancy than the reference group, but was not statistically

weeks), 18.5 weeks (1 – 100 weeks) for those who conceived

significant [HR 0.97 per kg/m2 below 21 kg/m2 (95% CI

and 31.5 weeks (2 – 146 weeks) for those without a pregnancy.